Domestic Farm Hogs vs Vietnamese Potbellied Pigs

For a long time it was thought that both the domestic farm hog and potbellied pigs were identical but through studies, some differences have been found. Their rectal temperature is one.

(click here for how to take temperatures of both domestic farm and potbellied pigs)

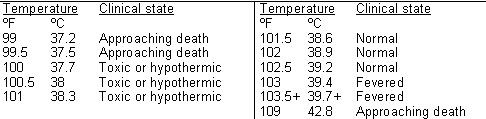

Domestic Farm Hog Temperature.

See copy of study on Vietnamese Potbellied pigs below. ( JAVMA Vol . 215 No 3 , Aug 1 , 1999 . )

RESTING RECTAL TEMPERATURE OF

VIETNAMESE POTBELLIED PIGS – Page 1

BY: LINDA K. LORD, DVM, MS;

THOMAS E. WITTUM, PH.D.;

DAVID E ANDERSON, DVM, MS;

DALE RIFFLE;

SARAH L LATHROP, DVM, PH.D.;

MARGARET A LAUDERDALE, MS

JAVMA, VOL. 215, NO. 3, AUGUST 1, 1999

Scientific Reports: Original Study

Objective:

To determine resting rectal temperatures of Vietnamese potbellied pigs.

Design:

Prospective clinical trial.

Procedure:

Rectal temperatures of the potbellied pigs on a farm were measured during the morning, afternoon, and evening. Rectal temperatures at the time of initial examination were obtained from medical records for the potbellied pigs examined at the hospital.

Results:

Mean rectal temperatures for both groups of potbellied pigs were the same. Overall unadjusted mean +/- SD rectal temperature was 37.6 +/- 0.8C (99.7 +/- 1.5F; range, 35.1 to 39.6 C [95.2 to 103.3 F] ).

However, diurnal variation in rectal temperature was found among the farm population of potbellied pigs. After adjustment for age and repeated sampling, rectal temperatures recorded during the morning were found to be significantly lower than temperatures recorded during the evening (mean difference, 0.4C [0.7F] ).

There was a significant inverse linear relationship between age and rectal temperature.

Conclusions and Clinical Relevance:

Rectal temperatures of Vietnamese potbellied pigs may be lower than the lower limit of the reference range reported for domestic pigs.

Because of diurnal variation in rectal temperatures, it is important to compare temperatures obtained at the same time of day where assessing patients. (J AM Vet Med Assoc 1999;215:342-344)

Vietnamese potbellied pigs were first introduced into the United States as companion animals in 1985. These animals have gained popularity as pets although accurate estimates of the number of potbellied pigs in the United States are not available.

Because these exotic pigs are the same species as domestic pigs (Sus scrofa), veterinarians commonly use reference ranges for domestic pigs when interpreting results of physiologic and hematologic tests preformed on potbellied pigs.

The reference range for rectal temperature of adult domestic pigs has been reported to be 38.6 to 39.7C (101.5 to 103.5 F). (1-3) However, our clinical experience has indicated that rectal temperatures of healthy adult potbellied pigs undergoing routine physical examination often are lower than this range.

Thus, we believe that potbellied pigs may have lower rectal temperatures than do domestic pigs.

The purposes of the study reported here were to determine resting rectal temperatures of Vietnamese potbellied pigs and to determine whether there was any diurnal variation in rectal temperatures of Vietnamese potbellied pigs.

Materials and Methods:

Pigs – Two populations of potbellied pigs were included in the study: One (farm population) consisted of potbellied pigs living on a single farm in Charles Town, WV. The farm operated as a nonprofit sanctuary for unwanted potbellied pigs, and had received potbellied pigs from throughout the United States.

Pigs were grouped into herds on the farm on the basis of size and temperament. Herds were housed in barns or small sheds with orchard grass hay for bedding. All pigs were fed a commercial swine finisher diet. All pigs on the farm were neutered.

The other population of potbellied pigs (hospital population) included in the study consisted of healthy potbellied pigs examined at the Ohio State University Veterinary Teaching Hospital during 1997 for routine veterinary care such as hoof trimming, tusk trimming, castration, or ovario-hysterectomy.

Rectal temperature at the time of initial examination, age, and sex were recorded, along with rectal temperature and age of these pigs during any previous hospital visits for routine veterinary care.

Procedures :

Rectal temperatures of the farm potbellied pigs were measured Sept. 12 and 13, 1997, using 3 digital thermometers. Prior to the study, the digital thermometers were tested in a controlled-temperature water bath and found to provide temperature readings within 0.06C (0.12F) of each other.

On days that rectal temperatures were measured, ambient temperature ranged from 15.0 to 25.6 C (59 and 78.1 F) and relative humidity ranged from 45 to 83%; there was no precipitation, but skies were predominantly overcast.

Rectal temperatures of the farm potbellied pigs were measured 3 times; the afternoon (between 4:00 and 5:45PM) of day 1, the morning (between 8:00AM and 12:00PM) of day 2, and the evening (between 6:50 and 8:00PM) of day 2.

Rectal temperatures were measured by 3 groups of 2 individuals, with 1 person in each group measuring temperatures and the other recording data.

During the first temperature recording session, recording personnel randomly selected pig herds to be used. Only pigs that were cooperative while recumbent or standing and did not require any restraint for rectal temperature measurement were used.

Rectal temperature was not recorded if the pig was perceived as stressed (e.g., pigs that resisted handling) by the procedure, appeared sick, or showed a change in appetite during the few days prior to the study.

During the remaining 2 temperature recording sessions, the same personnel measured rectal temperatures of the same pigs, using the same thermometers that had been used during the first session.

For each potbellied pig, the identification number, herd number, session, rectal temperature, personnel group, age and sex were recorded.

Statistical Analyses:

For the farm population, effects of time of day (session) and age on rectal temperature were assessed by use of multivariate ANOVA procedures for repeated measures. (4)

Variables initially included in the model were session, personnel group, sex, and age.

Factors not associated with rectal temperature were removed from the model by use of a backward elimination procedure, with a criterion of P< 0.05 for the factor to remain in the model. Potential interactions were tested and removed from the model if not associated with rectal temperature.

For the hospital population, effect of age on rectal temperature was assessed by use of ANOVA procedures for repeated measures.

Results:

The farm population consisted of 85 potbellied pigs (32 female and 53 male) selected from a total of 200 potbellied pigs on the farm. Age of the pigs ranged from 0.86 to 8.31 years ( mean +/- SD, 5.16 +/- 1.56 years).

Overall mean rectal temperature of the farm population was 37.6 +/- 0.8C (99.7 +/- 1.5 F; range, 35.1 to 39.6C [95.2 to 103.3F]).

Diurnal variation in rectal temperature was found; unadjusted mean rectal temperature varied from 37.2 +/- 0.8C (99.0 +/- 1.5F; range 35.3 to 38.6C [95.5 to 101.5F]) in the morning to 37.7 +/- 0.7C (99.9 +/- 1.3F; range, 35.1 to 39.2C [95.2 to 102.6F]) in the afternoon to 38.1 +/- 0.6C (100.6 +/- 1.0F; range, 36.3 to 39.6C [97.3 to 103.3F]) in the evening.

After adjustment for age and repeated sampling, rectal temperatures recorded during the morning were found to be significantly (P < 0.001) lower than temperatures recorded during the afternoon and evening (mean difference, 0.5 and 0.9C [0.9 and 1.6F], respectively), and rectal temperatures recorded during the afternoon were found to be significantly ( P < 0.001) lower than temperatures recorded during the evening (mean difference, 0.4C [0.7F]).

We identified an inverse linear relationship between age and rectal temperature, with rectal temperate decreasing significantly (P < 0.05), as age increased. Differences attributable to herd, sex and personnel group did not describe a significant amount of the variability in rectal temperature and did not remain in the final model.

The hospital population consisted of 27 potbellied pigs (9 females and 18 males). A total of 75 separate visits was recorded for these 27 pigs, with 22 visits (29%) involving sexually intact pigs. Age at time of examination ranged from 0.13 to 8.09 years (3.72 +/- 2.01 years).

Mean rectal temperature was 37.6 +/- 0.8C (99.7 +/- 1.5F; range, 34.8 to 39.1C [94.6 to 102.4F]). Significant differences were not found between mean rectal temperatures for male and female pigs (P = 0.82) or between sexually intact and neutered pigs (P = 0.06; Student t-test). Age was inversely related (P < 0.05) to rectal temperature.

The consistency of findings for these study populations supports the hypothesis that Vietnamese potbellied pigs may have lower rectal temperatures than the reference ranges reported for domestic pigs, particularly because one population consisted of potbellied pigs living in a nonstressful farm environment and the other consisted of potbellied pigs exposed to the stress of routine procedures performed in a veterinary hospital environment.

This suggests that the reference range for rectal temperature in domestic pigs may be inappropriate for potbellied pigs.

We observed diurnal variation in rectal temperatures of the farm population of potbellied pigs in this study, with the highest temperatures recorded during the evening.

Diurnal variation in body temperature has been documented in other animal species, with as much as a 1.0C (1.8F) difference between morning and late afternoon temperatures. (5)

Diurnal variation in core body temperature has also been documented in humans, with variations of 0.5 to 0.7C (0.9 to 1.3F) reported as normal. (6)

Lowest temperatures reportedly are recorded at approximately 6:00AM, with higher temperatures recorded in the evening, which is similar to our findings.

Although diurnal variations in rectal temperatures of animals are recognized, they are not typically emphasized in veterinary clinical settings. However, it is important to recognize that daily variations in body temperatures are normal for animals, particularly when monitoring temperatures of sick animals and when using body temperatures as a test to screen for disease.

Studies in humans have emphasized the importance of standardizing the time of day at which temperature is assessed. (7)

Our results suggest that it is important to compare temperatures taken at similar times of day when assessing serial rectal temperature readings in potbellied pigs. Failure to do so may lead to erroneous conclusions about the health of an animal.

In this study, we also found that age was inversely related to rectal temperature. Higher temperatures are generally expected in young, growing animals. (1)

In a study (8) of Beagles at rest, mean resting rectal temperature of young dogs (5 to 7 years old) were not significantly different from those of old dogs (7 to 10 years old). However, the limited range in dog ages and the definition of “young” versus “old” may have been an inefficient method of detecting an age effect.

Rectal temperature of many species may decrease with age because of a decrease in activity and a corresponding decrease in metabolic rate.

Further studies that investigate the relationship between age, rectal temperature, and thyroid function might be useful in determining whether a decrease in metabolic rate is associated with a decrease in metabolic rate is associated with a decrease in rectal temperature in older pigs.

On the basis of our results, we believe that the expected rectal temperature of potbellied pigs should be 37.6C (99.7F), which is approximately 1.0C (1.8F) lower than the lower limit of the reference range for domestic pigs. (1-3)

Variations of 0.5 to 0.9C (0.9 to 1.6F) attributable to time of day and age should be expected.

Although all the pigs in the farm population were neutered, we did not detect any differences in rectal temperatures between sexually intact and neutered pigs in the hospital population, or between male and female pigs in either study population.

It is possible that the difference in rectal temperature between domestic and potbellied pigs relates to the difference in lineage. Domestic pigs have been genetically selected for productivity and maximal weight gain. This has resulted in large-framed, lean pigs that rapidly gain muscle mass.

Potbellied pigs, however, have evolved in a different environment. They are a source of meat, manure, lard, and family income for many families in Vietnam. (9)

Pigs are kept for many years, and it is not uncommon for a sow to exceed 10 parties. These pigs live on aquatic plants and rice, and have very fatty carcasses. The fat is valued in a society in which the staple human diet has traditionally been rice.

These differences in productivity and environment may have caused domestic and potbellied pigs to evolve different thermoregulatory mechanisms. Further studies are indicated to determine rectal temperature differences in domestic and potbellied pigs.

References

1. Straw BE, Meuten DJ. Physical examination. in: Leman AD, ed. Diseases of swine. 7th ed., Ames, Iowa; Iowa State University Press, 1992-795

2. Fraser CM. The Merck veterinary manual. 7th ed. Rahway. NJ: Merck & Co Inc, 1991-966.

3. Taylor DJ. Pig diseases. 5th ed. Cambridge, UK: The Burlington Press, 1989.6.

4. SAS/STAT software: changes and enhancements through release 6.12. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc. 1997:573-701.

5. Radostits OM, Blood DC, Gay CC. Veterinary medicine 8th ed. London: Bailliere Tindall, 1994;15.

6. Ganong WF. Review of medical physiology. 18th ed. Stamford, Conn: Appleton & Lange, 1997; 234-235.

7. Schellengerg JRMA, Greenwood BM. Gomex P, et al. Diurnal variation in body temperature in Gambian children. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 1994; 88, 431-432.

8. Strasser A. Simunek M. Seiser M. et al. Age-dependent changes in cardiovascular and metabolic responses to exercise in beagle dogs. Zentralbl Veterinarmed [A] 1997; 44, 449-460.

9. Porter V. Pigs: a handbook to the breeds of the world. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1993; 185-189.

From the Departments of Veterinary Preventive Medicine (Lord, Wittum, Lathrop, Lauderdale) and Veterinary Clinical Sciences (Anderson), College of Veterinary Medicine.

The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio 43210: and PIGS Inc, PO box 629, Charles Town, WV 25414